In 2011, my family and I went to the San Jose Museum of Art and made sugar skulls as part of their community day celebrating Dia de los Muertos. As we pulled them out for our Halloween decorations this year, Kelly was nostalgic, and asked to do it again.

This year, the festivity took place on November 2, after Halloween, but accurately in time for the Catholic celebration, which took place on November 3 this year. This year, the art museum’s event was busier than ever. Kelly brought along her friend Laralai, and both of them posed with a dancing skeleton as we waited to check in:

With the sugar skulls being our primary goal, we got into another line to wait for a place at a table where we could decorate the skulls with frosting, feathers and sparkly bits. More than a few people had dressed up for the event:

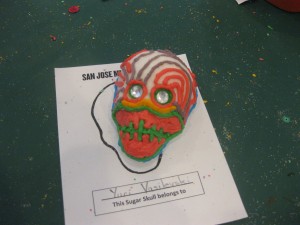

At the tables, everyone had their own design ideas for sugar skulls; the key to a good sugar skull design is a complete lack of restraint on color or bling. Make it bold! Make it happy! And make it your own! I thought this one was particularly well crafted. Mine had feathers and as much sparkle as could make sense. Kelly’s skull was sad, because she was dead (but as we found out later, was the skull really dead?)

After we were done with our sugar skulls and had set them aside to dry, the girls made paper flowers, and butterflies. A mariachi band played cheery music in the museum’s main entrance, where 4 catrinas, including these two, stood around the windows:

A giant skeleton also graced the main floor:

Ever since I stumbled across the Dia de los Muertos display at St. Jospeh’s basilica across the street, however, one of my favorite exhibits for the holiday is the one they set up in a church alcove. I failed to find it in 2012, because, as I discovered this year, it’s not a month-long display — it is only set up for the day itself.

I insisted the girls come with me to check it out. We discovered the ofrendas were simply in the process of being set up, but one of the volunteers who was working on them told us about Dia de los Muertos, which was even more informative than the poster which had told me about its Aztec origins in 2011.

We learned that the indigenous people believed everyone went through three deaths: the death when your body dies, the death when your body is interred, and the death when everyone forgets about you. With these memorials, the souls don’t experience the third type of indigenous death, and even though the Catholic tradition holds that the souls have gone to heaven, it allows us to celebrate those who have gone before us. The girls asked about the f0od on the altars, and we learned that the spirits had a long journey to come back, so they’d be hungry and they’d “eat” the food. There is a also a rug because their feet are sore after the long journey, and marigolds with a particularly strong scent to help them find their way.

The people being honored with pictures and former favorite possessions don’t have to be family members — if someone doesn’t have a family to remember him or her, anyone may add him. In Mexico, the altars are normally set up in people’s homes, but the basilica has a few (very large ones) set up for the festivities.

Kelly thought all the skulls and skeletons were spooky.

But the effect is meant to be quite the contrary. By memorializing those who have passed on, we laugh at death, because it doesn’t have the ultimate power over us.

Over in the church kitchen, other volunteers were making traditional foods by hand for the festival. Some of the Catholic parishes in San Jose were also having midnight services at some graveyards, including Oak Hill near us. The next day, the real feast would go on, in conjunction with All Souls’ Day, and we were invited to come and to see the ofrendas when they were all set up.

After that, we had to head home, as the event at the art museum began to wrap up. On our way back to our garage, we saw the bride and groom come out from a wedding at the basilica, which was a fitting end to our celebration of the Day of the Dead.